Since Covid-19’s sudden interruption of the continuous growth of touristic mobilities, several researchers have reflected on how to rethink tourism. French Sociologist Jean Viard argues that “from this pandemic must appear a Global Tourism Code”. Accordingly, tourism must be constrained by regulations to avoid pollution and the destruction of nature and local cultures. If tourism is initially a cultural exchange project, mass tourism brings with it a certain amount of “perverse effects” at diverse levels, namely negative effects on the environment and on the daily lives of the inhabitants – who are, in a way, dispossessed of their habitat – and the cancelling of the traveller’s experience, given that the crowd of tourists can provide a negative effect on the experience itself.

Not ignoring the importance of the two first levels, this article focuses on the last level: the conditions of the experiences. However, to summarise the propositions to neutralise the negative effects of tourism on the environment and communities’ daily lives, it is crucial to emphasise the importance of the awareness of the environmental problem.

First, the political/economic powers have the possibility to manage and regulate the flow of tourists to avoid pollution and overcrowding. Second, the responsible individual, traveller/tourist and the local inhabitant, tend to act accordingly to respecting the environment, namely through consuming/producing local and biological products with less waste and choosing/proposing less energy-consuming activities. Collaborative design can provide sustainable transformation of the tourism introducing the “notion of designing with, rather than developing for“.

To avoid a negative impact on daily life, authorities (states, cities, villages and other local entities) can impose rules. Accordingly, Denmark has legalised the right to access properties to prevent speculation by foreigners (e.g. Germans buying summerhouses) only if they can guarantee a special attachment to Denmark. Eighteen cities in France, including Paris, have imposed owners no more than 120 days of rental through Airbnb to avoid ghost areas in the city, etc.

A proposal that combines the concern for the environment with the mutually beneficial exchanges between traveller/tourist and the inhabitant, could be to design joint participatory projects (e.g. a village may wish to organize a tree planting during the touristic season) so that the traveller/tourist becomes a responsible citizen of the world and leaves a constructive trace of their presence in the places they visit.

Combining the respect for the environment and the time to contemplate the surroundings and to meet other people, “slow tourism” proposes a framework for “meaningful” experiences. Furthermore, “creative tourism” invites the visitor to use all five senses to learn the artistic expressions of the local culture. In “collaborative design”, “participatory project”, “slow” and “creative” tourism, the experience seems to become the central pivot for the signification of mobility.

In the following, I will explore the different conditions of tourism and travelling and the possible noetic dimension of the experience with a potential transformation of the ‘Self’.

Differentiating Tourism from Travelling

Ever since tourism research emerged in the seventies, the academic field has discussed its key concepts. As an evidence, the field became transdisciplinary, encompassing history, geography, economy, political sciences, anthropology and sociology. Every discipline is using its own vocabulary, even though the complexity of the phenomenon, seems to require transversal research and operational definitions.

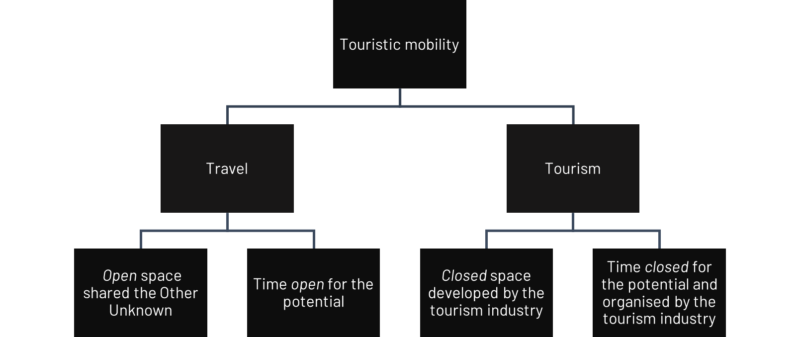

Thus, I propose two definitions: one for the tourist and one for the traveller, using the time and space conditions to distinguish these two. Currently, this differentiation is not used as most researchers tend to consider the tourist to be a traveller and the traveller to be a tourist as the nature of touristic mobility is viewed to be constant.

Even if the traveller and the tourist have in common the desire of ‘Elsewhere‘, they do not live the same time and space conditions and consequently, their experiences differ.

To illustrate the difference, I have defined two ideal types of touristic mobility:

In travel, the traveller lives in an open space shared with the ‘Other Unknown’, the inhabitant of the place visited, and time is open for the potential of spending time with something (an object of contemplation) or someone (a subject) of interest for the traveller. In tourism, the tourist is constrained in a closed space developed by the tourism industry, experiencing a closed time for the potential that is organised.

Rachid Amirou notes that certain individuals “Elsewhere” from their everyday life, find themselves in what he identified as a “touristic bubble”, in a closed time and space (e.g. Club Med). Space is closed as the tourist is, in an area that includes all activities for the stay (e.g. sleeping, eating, staying by the pool or beach, doing sport, having parties, etc.). Time is closed since it is organised and managed by the service provider according to a proposed program.

This protected touristic bubble is constructed by the industry in order to offer a product that contains all the tourists’ needs (relaxation, entertainment and development, as defined by Dumazedier). Based on that, I have extended the concept to what I call the touristic corridor, where the tourist moves from point A (accommodation) to point B (e.g., museum visit) to Point C (e.g. shopping), etc. The fundamental aspect of this organisation is that the tourism industry has to deal with flows since profit is the main concern.

This Manichean panorama must be nuanced. First, the distinction between traveller and tourist is schematic. However, this reductive process has the virtue of making these working figures operational for research on tourist mobility. As ideal types, it means that the tourist can, at times, leave the tourist circuit and the traveller can re-enter it. In addition, there is no value judgment: the traveller does not have all the qualities and the tourist all the faults, but in relation to their differentiated conditions they do not have the same experiences.

The Experience

When defining the experience, Belgian sociologist Emmanuel Belin states that the “experience is what, from within, we integrate the outside and, from the outside, the inside. And the mediation is what makes this interpenetration possible”. An experience happens when something from the outside relates to the inside.

According to French sociologist Antigone Mouchtouris, an aesthetic experience depends on a noetic function with a dynamic temporality with a distinctive moment before (n) and a moment after (n’) instigated by a new vision of the world. This mechanism is valid for art, but also for face-to-face interaction with the ‘Other Unknown’ or ‘Elsewhere’. The observed object transmits information that can provide another point of view. The experience with a noetic function requires time for mediation, a space with a proposition from the ‘Other’ and a present mind.

The central hypothesis, validated in my PhD, is that the traveller in open space-time, who experiences more noetic moments than the tourist in a closed space-time who lives only what is given to him. To illustrate this hypothesis, it was assumed that the Danes studied in the Aude mainly represent the ideal type of traveller and the Chinese studied in Paris mainly represent the ideal type of tourist.

The Condition of the Tourism Experience

According to German philosopher Emmanuel Kant, the world is perceived by the individual through two transcendent conditions: time and space. For perception, time is indefinite, and space is definite. The time spent in one space is dependent on the rest of the movement of the individual. Space is the field of possibilities. Touristic mobility allows the individual to experience the ‘Otherness’ and new models. The “object in itself” is what the object really is in totality. The individual observes the object with her/his subjectivity and thus sees the object only partially. An experience does not mean that the subject has the full perception of the object, but that a part of the object understood by the subject enters the individual. Consequently, one can identify three decisive conditions of an experience: time, space and the interaction between subject and object depending on the uptake of the individual observing.

Time

The object is observed by the subject with her/his own subjectivity, hence seeing the object only partially. However, time spent with an object allows a vision “closer” to the “object itself”, rather than when the individual crosses the space without allowing himself the time for the observation of the object or is occupied by something else (e.g. by a screen). In my research on tourist mobility, I have observed several temporalities: slow time versus fast time and time of availability to the object and time of non-availability.

According to sociologist Georges Gurvitch, each social unit has its own temporality. That is, each ‘We’ constructs time in its own image, but within a unity, a multiplicity of time can exist. The concept of multiple time is of particular interest since the individual needs indeterminate time for a noetic experience, e.g. an artist who looks at a work of art by another artist can probably grasp the vision of the ‘Other’ quite immediately, whereas a novice may need more time for the object to transmit another vision of the world.

Generally, the stay of the Chinese tourist in Paris is short. According to Le Tourisme à Paris. Chiffres clés 2016, Chinese tourists spend an average of 2.33 days in Paris.

Observed in my Research:

In the questionnaire, three Chinese women (staying 2-3 days) express their dissatisfaction with the time it takes to discover Paris and the exceptional positive feeling, such as joy when describing their stay. These examples show that there is, among some Chinese, the desire for a longer-term commitment.

When Chinese tourists visit a museum, they move as one body through the space. Some visits are very quick (the shortest observation was 30 min. for a group visiting Le Louvre) and some are significantly longer (the longest was 1h and 30 min. in Le Louvre). When visiting, Danish travellers are living a multiple time where each individual can contemplate an object according to his interest. The result is an explosion of the group in the visited space. Even for groups, the Danes tend to have no strict time schedule.

Mostly, Danes are living the time rhythm of Aude (they stayed on average 11.5 days there). Danes questioned during interviews experienced a noetic function in relation to time. They found time in Aude “slower” and appreciated the personalisation of social relationships seen in the public space, where the time available for each individual was considered pleasant.

An anecdote attests to friendship building with the French when a Danish couple was able to adapt to this open time (e.g. mealtime depends on guests arriving unexpectedly). This experience had an impact on daily life, as the Danish couple exported this temporal spontaneity to their country of residence. These travellers learned a “lesson”, through noetic function, about the quality of slow and open time, during their trip to France. In general, it has been observed that the Danish traveller seeks this local rhythm as a beneficial temporal parenthesis, precisely because of its slowness. A Danish woman revealed that she was searching for “lots of unforeseen things”. The meaning of travel is for her an absent structure, a space-time where nothing is planned and where everything is possible.

Space

Sociologist Maurice Halbwachs establishes that space is created by social life and at the same time is creator of social life. He writes in La Mémoire collective: “Thus each society divides the space in its own way”. In short, space conditions social forms and possible activities.

No Chinese tourist interviewed has taken an alternative itinerary. Every Chinese mentioned the same places: Le Louvre, the Eiffel Tower, Notre-Dame de Paris, the Arc de Triomphe, the Tuileries Garden, the Palace of Versailles, Montmartre and the Moulin Rouge. These itineraries do not go outside the tourist corridor.

During my observations at the Louvre, I noticed that the itinerary differs from group to group. However, some places are visited by groups guided in a ritualistic way: La Joconde, Les Noces de Cana, Le Sacre de Napoléon, La Victoire of Samothrace and Aphrodite known as La Venus de Milo. Nonetheless, self-guided tours, from small groups to one person, visited other areas of the museum not visited by groups, such as Egyptian Antiquities, Oriental Antiquities and the medieval Louvre. This shows that the tourist corridor is enlarged by individuals.

The Danes observed in Aude settle down for a longer stay and they frequent the same places as the inhabitants (e.g. they shop in the same stores). They take possession of daily life, sensorially immersing themselves in the space of the locals. In the interviews, the Danes reveal their desire to “blend in”. One can establish that in this case, the space is open.

The “experience Elsewhere” is a notion often cited in the answers on the meaning of travel. The experience is a source of inspiration for the individual, it offers the possibility of a noetic function with reflectivity on the ‘Self‘. The search for the ‘Self’ abroad is evoked by a Danish man who seeks a journey to “live the foreign culture, see nature and live in the other of the new”. Another Danish-Canadian man expresses that, individuals ultimately seek only “themselves”, as if they are travelling to discover humanity’s diversity in a world that is only a mirror of their potential being.

The Interaction Between the Subject and the Object

The relationship between subject and object is a dynamic process that depends on the space and time available. The object of the travelling subject can be another object (a painting or a Vuitton bag) or another subject; the Other Unknown. In the latter, learning the ‘Other’ goes through the channel of verbal and/or non-verbal communication.

During my fieldwork, I have seen that interactions with ‘Other Unknowns’ depend on the context.

In the limited space-time of the Chinese tourist in Paris, interactions with the ‘Unknown Other’ occur very little, except briefly during times before or after the visit to get tickets or to eat. And even these moments of exchange are increasingly rare as the tourism sector employ Asian people to guide and serve them (e.g. Le Louvre and Galleries Lafayette).

Generally, for the Danes in the Aude, the exchanges are done mainly around daily routines (e.g. buying food). However, when a particular event is proposed (e.g. the harvest) they observe the ‘Other Unknown’ and imitate them (e.g. kissing a winegrower to thank him for the day, mimicking his relatives). The Other Unknown becomes the Other Known, and friendships are built with time spent together.

By virtue of my observations, I can infer that the Dane is a traveller in an open space-time during her/his stay in Aude and that the Chinese is mainly a tourist staying in a closed space-time during her/his visit to Paris. Furthermore, Danish travellers tend to experience more the noetic function than the Chinese tourist, but the last quoted develops towards more individual travelling and thus outbreaking more from the touristic corridor.

Noetic Experiences and Innovation

Tourism products are built by the industry and according to profitability criteria (fast time, group travel and imposed organisation), while travel is built according to the choice of the traveller and the opportunities presented (multiple time, variability possible), making travellers available for exchanges with other subjects or for object contemplation.

The traveller is an ideal type who accesses the unknown in an open space-time, being engaged in the project of understanding the ‘Elsewhere’ and the ‘Other Unknown’ in-depth, through a constructive dialogue between the ‘Self I’ and the ‘Other’. The ‘Self I’ is a concept developed by American sociology George H. Mead to describe the possibility of the emergence of a reflective, creative and distinct ‘Self’ from the socially conditioned reproductive ‘Self Me’.

On the contrary, the tourist is an ideal type who searches for the most known possible in a closed space-time and who passes quickly in space without being subjectively engaged, remaining at a distance from the ‘Otherwise‘. Therefore, consolidating the ‘Self Me’, since the ‘Elsewhere’ and the ‘Other Unknown’ do not penetrate him. In other words, objects/subjects ‘Elsewhere’ can be sources of inspiration, rejection and ignorance.

Nevertheless, it is the noetic experience that builds the traveller, not the individual’s social determination. The common space of both traveller and tourist allows for a mirror effect. Through emulation, today’s tourist is potentially a future traveller.

In fact, moving around in an open space-time can be favoured by tourism institutions. Noetic innovation would be to offer the individual tourist/traveller a space that would be considered as an investment, the necessary time of mediation between him and the object of contemplation. Thus, space-time conditions could be more optimal in places of visit (those not equipped with digital screens but e.g. comfortable furnishings, live music, paper and pencils distributed to anyone who would like to express themselves through drawing or poetry) for the individual to take part in noetic experiences.